Extollager

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2010

- Messages

- 9,055

Somewhere I have seen some non-Russian reader exclaim with wonder about why Russians write such good autobiography. Here's a place to discuss any such writing, including writing by authors who were born in what's now Ukraine, etc. I'll introduce four of these writers below, but I hope we can discuss others as well.

Sergei Aksakov (1791-1859) wrote a trilogy I recommend warmly (particularly the middle volume): A Russian Gentleman, Years of Childhood, A Russian Schoolboy. My understanding is that J. D. Duff's translations are considered to be remarkably good. These were issued in Oxford World's Classics editions a while ago. In English we also have Notes of a Provincial Wildfowler and Notes on Fishing.

Sergey Aksakov - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)

I haven't read much yet by this author, but I enjoyed his Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev.

Maxim Gorky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870)

I liked Childhood, Youth, and Exile a fair bit.

Alexander Herzen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

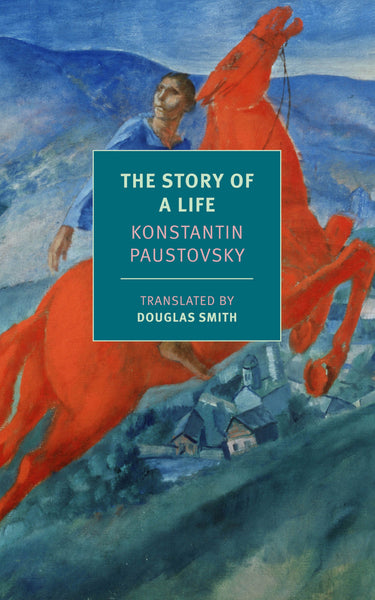

Konstantin Paustovsky (1892-1968)

He wrote Story of a Life in six volumes, which were published in England by Harvill some years ago. I am rereading the first volume, Childhood and Schooldays, with satisfaction right now, and expect to continue from it to the next volume. I have the whole set, but I haven't seen a lot about it, so I'm not sure it will prove to hold my interest throughout all of the books.

Konstantin Paustovsky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

It sounds like the whole set of books will prove to be worth reading:

venus febriculosa» Blog Archive » konstantin paustovsky, the story of a life

Sergei Aksakov (1791-1859) wrote a trilogy I recommend warmly (particularly the middle volume): A Russian Gentleman, Years of Childhood, A Russian Schoolboy. My understanding is that J. D. Duff's translations are considered to be remarkably good. These were issued in Oxford World's Classics editions a while ago. In English we also have Notes of a Provincial Wildfowler and Notes on Fishing.

Sergey Aksakov - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)

I haven't read much yet by this author, but I enjoyed his Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev.

Maxim Gorky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870)

I liked Childhood, Youth, and Exile a fair bit.

Alexander Herzen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Konstantin Paustovsky (1892-1968)

He wrote Story of a Life in six volumes, which were published in England by Harvill some years ago. I am rereading the first volume, Childhood and Schooldays, with satisfaction right now, and expect to continue from it to the next volume. I have the whole set, but I haven't seen a lot about it, so I'm not sure it will prove to hold my interest throughout all of the books.

Konstantin Paustovsky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

It sounds like the whole set of books will prove to be worth reading:

venus febriculosa» Blog Archive » konstantin paustovsky, the story of a life