What I had in mind is the characteristic tendency of much modern thinking to say that something is "nothing but" something less alive, less free, more mechanical. E. F. Schumacher writes about this in

A Guide for the Perplexed. The trajectory is to eliminate ever more thoroughly the specifically human. The ultimate destination is that all causes are materialistically determined, that is, products of non-rational factors that have nothing to do with human values. Dennett sounds like the kind of reductive thinker I have in mind:

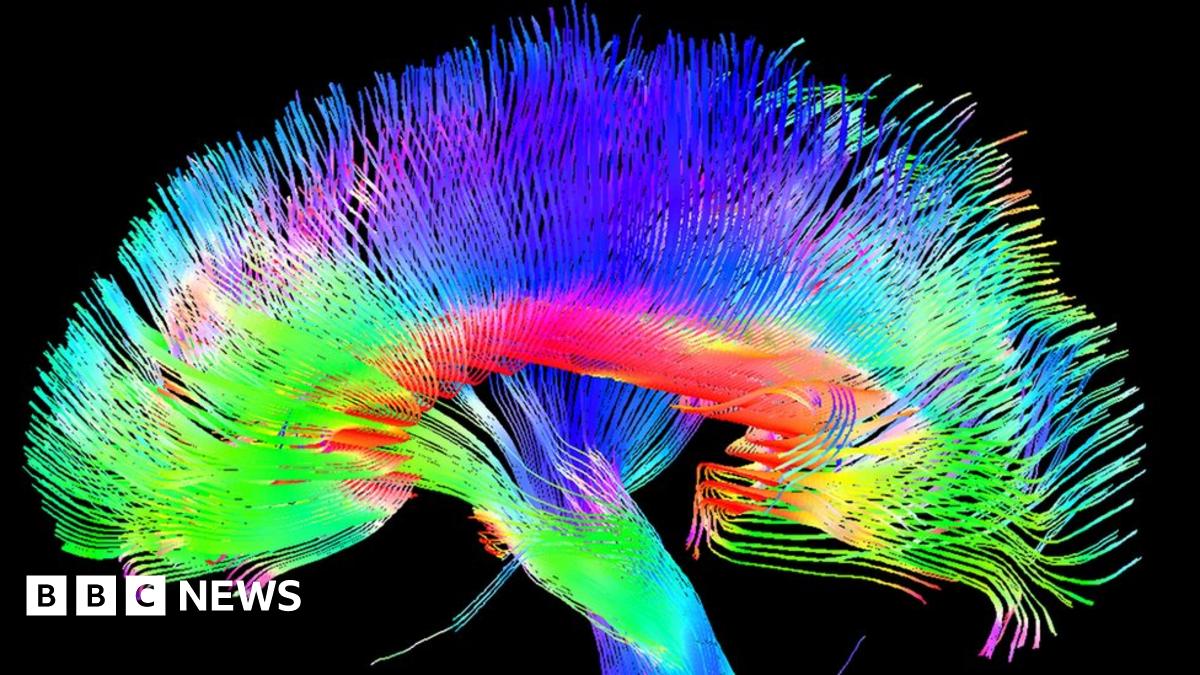

Cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett believes the human brain might not be that special.

www.bbc.com

(to say nothing of less accomplished thinkers)

The kind of philosophy I have in mind might start with our experience of ourselves as self-aware creatures, capable of empathy, etc. The human difference over against other animals is profound. A simple way of putting it is like this:

rocks and minerals exist; the only way they can be said to reproduce is by crystal growth, so far as I know, since they are not alive

plants are alive and reproduce, altering their environments by breaking them down

animals are alive, reproduce, are conscious, and alter their environments by making them more orderly than before

humans are alive, reproduce, are conscious, are self-aware, and alter their inner world through exercise of choices, e.g. to learn a language, to subject themselves to increasing exposure to frightening things in order to overcome their fears, as well, harmfully, as willfully impairing their consciousness by drug abuse, etc. Animals (nonhuman) may be deceived but they do not deceive themselves. An animal may feel pain from cancer but it doesn't tell itself it's just a case of the flu (the way Lovecraft did when his cancer symptoms were worsening, as I remember). Humans value things that are of no adaptive advantage as well as ones that are. For example, many people feel quite strong aesthetic emotions at the sight of sunset over a mountain range. If they were there in those mountains food might be scarcer, the climate harsher, etc.

A reductive philosophy must find some way to explain away (or to ignore) such emotions, but isn't likely to convince those not already convinced on other grounds.

But these are only thoughts on one or a few aspects of the matter of non-reductive philosophy.

Animals possess intelligence, but so far I'm not aware of claims for particular

animal geniuses. But genius is a "common" feature of humanity. By "genius" I mean, or would include, the capacity to make excellent choices, more or less simultaneously, in some endeavor. For example, a poet calls upon memory (personal experience [perhaps including dreams as well as wakeful experience], historical knowledge, experience of others as imparted by film, painting, writing, music, whatever), verbal skill (vocabulary, diction, semantics, the dimension of language including pure sound), etc. -- more or less all together in the composition of a poem. As Schumacher argues, then, uniquely with humans it is the exceptional that "defines" the species.

Reductive philosophy will probably prefer to focus on "the norm," usefully generalized.

Non-reductive philosophy will want to take into account

historical consciousness. Animals have no history though they may have an evolution. Now, what does it mean to possess historical consciousness? Non-reductive philosophy might want to explore this. (There's a book by John Lukacs that probably would help me on this topic.)

What makes for true development in the arts -- and also what makes for false or harmful directions in the arts? I think NR philosophy would explore this question more interestingly than reductive philosophy. Logical positivism was reductive in its doctrine that only empirically verifiable statements were meaningful. I wouldn't expect it to be helpful in a philosophical evaluation or exploration of poetry, for example.

Glancing at a Wikipedia article on Nikolai Berdyaev (whom basically I haven't read), he sounds like a non-reductive guy. For him creativity, love, and relationship are key concepts. On hand I have Martin Buber's

I and Thou, which I think will be a good example of what I'm after.

Below: Buber, Schumacher.