Extollager

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2010

- Messages

- 9,057

I've been delving into Tolkien's work (unpublished in his lifetime) of the second half of the 1920s and well into the 1930s, and commented on some poems by his friend C. S. Lewis here:

http://www.sffchronicles.co.uk/foru...e-earth-50-pages-per-month-6.html#post1786676

An important part of the context of Tolkien's creativity -- one underestimated by some of his fans -- was the shared interest in fantasy of his fellow scholar and friend. If I'm not mistaken, when Tolkien first shared some of his "Silmarillion" writings with Lewis, it was in the form of poetic efforts, and at about the same time Lewis was writing fantasy in the form of narrative poetry too. His works in this form include

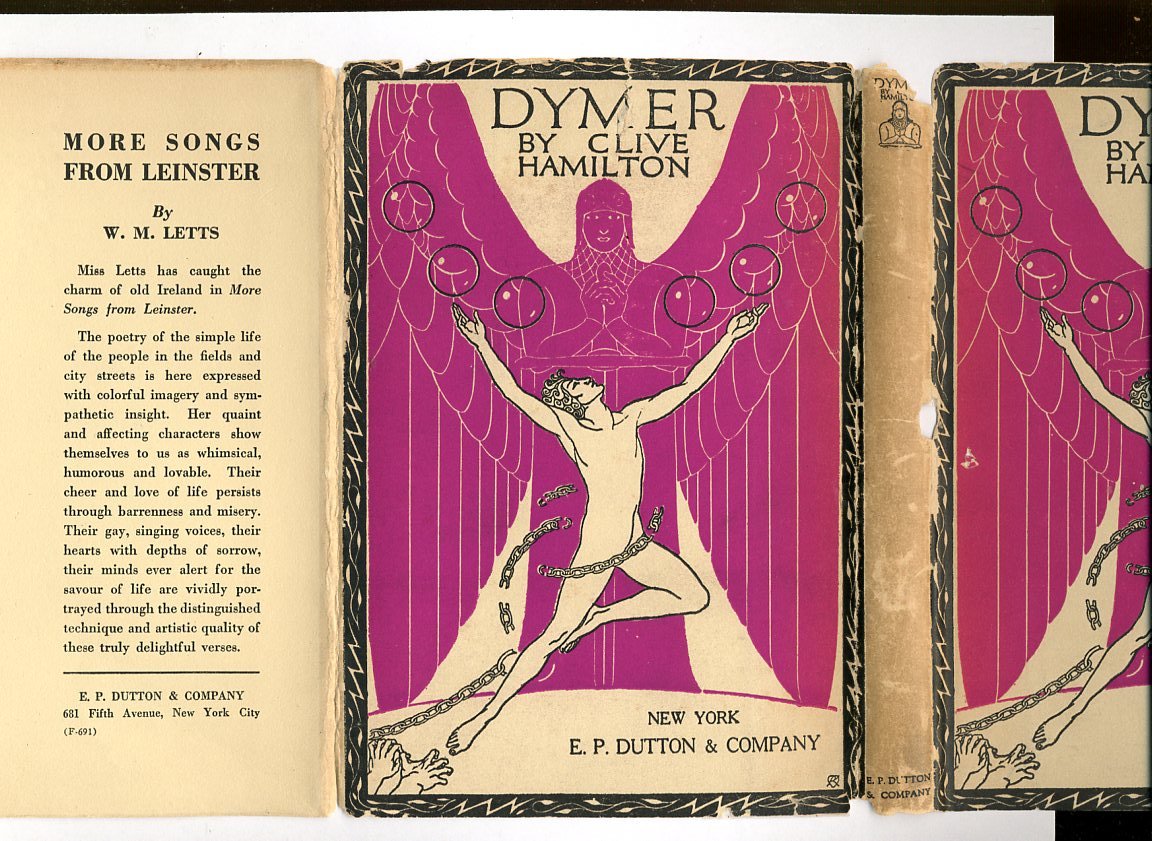

Dymer (a new myth, published pseudonymously in 1926 before Lewis's Christian conversion)

Launcelot

The Nameless Isle

The Queen of Drum

They are all in the book Narrative Poems. If you are interested, you might want to get a used copy, as it appears that the publisher now issues the book as a less-attractive print-on-demand edition.

I propose to comment on some or all of these poems here and hope others will discuss them with me. I would like to keep them in the context of Tolkien's creative work of the time. Both men, for example, are writing in the vein of Northern-inspired myth and legend ... and yet "Nameless Isle" is, if memory serves, an unrecorded adventure of Odysseus -- ? No; some other mariner, I guess. A beautiful "witch-hearted queen" nurses the creatures of the wood -- beasts and creeper-plants -- at her breasts; a "hunched and hairy" dwarf and a marble maiden appear....

There's some fine sensory imagination in these poems.

They should be a good detour from Tolkien for a few days. Tolkien's and Lewis's poetical works of this period represent a major part of what they were up to prior to Lewis writing his space trilogy and Tolkien starting The Lord of the Rings!

http://www.sffchronicles.co.uk/foru...e-earth-50-pages-per-month-6.html#post1786676

An important part of the context of Tolkien's creativity -- one underestimated by some of his fans -- was the shared interest in fantasy of his fellow scholar and friend. If I'm not mistaken, when Tolkien first shared some of his "Silmarillion" writings with Lewis, it was in the form of poetic efforts, and at about the same time Lewis was writing fantasy in the form of narrative poetry too. His works in this form include

Dymer (a new myth, published pseudonymously in 1926 before Lewis's Christian conversion)

Launcelot

The Nameless Isle

The Queen of Drum

They are all in the book Narrative Poems. If you are interested, you might want to get a used copy, as it appears that the publisher now issues the book as a less-attractive print-on-demand edition.

I propose to comment on some or all of these poems here and hope others will discuss them with me. I would like to keep them in the context of Tolkien's creative work of the time. Both men, for example, are writing in the vein of Northern-inspired myth and legend ... and yet "Nameless Isle" is, if memory serves, an unrecorded adventure of Odysseus -- ? No; some other mariner, I guess. A beautiful "witch-hearted queen" nurses the creatures of the wood -- beasts and creeper-plants -- at her breasts; a "hunched and hairy" dwarf and a marble maiden appear....

There's some fine sensory imagination in these poems.

They should be a good detour from Tolkien for a few days. Tolkien's and Lewis's poetical works of this period represent a major part of what they were up to prior to Lewis writing his space trilogy and Tolkien starting The Lord of the Rings!

Last edited: