Extollager

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2010

- Messages

- 9,055

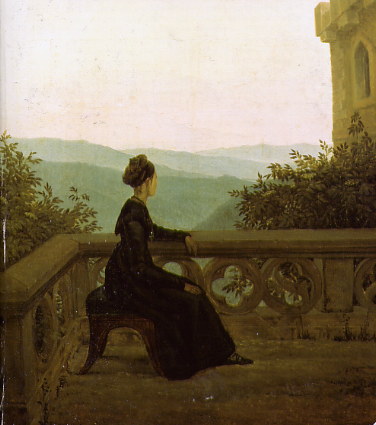

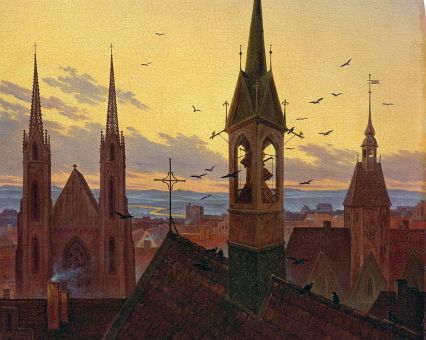

This thread ought to attract a few Chronsfolk, who've delved into the traditional "Gothic" novel, of which Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823) was perhaps the most accomplished exponent.

I confess that the most I've managed thus far was the reading of perhaps a third of Mysteries. However I'm pretty sure that, at least, J. D. Worthington has read extensively in Radcliffe's novels.

My favorite artist, Samuel Palmer, and his friends enjoyed Mrs. Radcliffe's romances when they were young, and there's a story of them setting off for a long walk by night to go to some neighboring village where they hoped to get hold of one of her books.

Some stir of conversation about her books might get me to pick up the one I started and persevere with it!

I confess that the most I've managed thus far was the reading of perhaps a third of Mysteries. However I'm pretty sure that, at least, J. D. Worthington has read extensively in Radcliffe's novels.

My favorite artist, Samuel Palmer, and his friends enjoyed Mrs. Radcliffe's romances when they were young, and there's a story of them setting off for a long walk by night to go to some neighboring village where they hoped to get hold of one of her books.

Some stir of conversation about her books might get me to pick up the one I started and persevere with it!